New UCAS historical entry grades data: Just how useful is it?

For the very first time UCAS have introduced information on their website that attempts to show you what grades students actually had when they entered different courses, rather than just showing the university’s published entry grades.

Nearly 50% of students, you see, get into their course with qualifications below the level of those published by the universities.

So when a course says you need AAB to get in, it turns out, you don’t!

This new data is aimed at making this all a bit clearer and more transparent, so that you can make better decisions about which courses to apply to.

Simple right? You know what students needed to get in in the past, so you can choose the right course depending on what you expect to get?

Well, not quite. Data can be a tricky thing, not easy to present clearly, and not easy to read accurately.

I’ll try to explain…

What’s included?

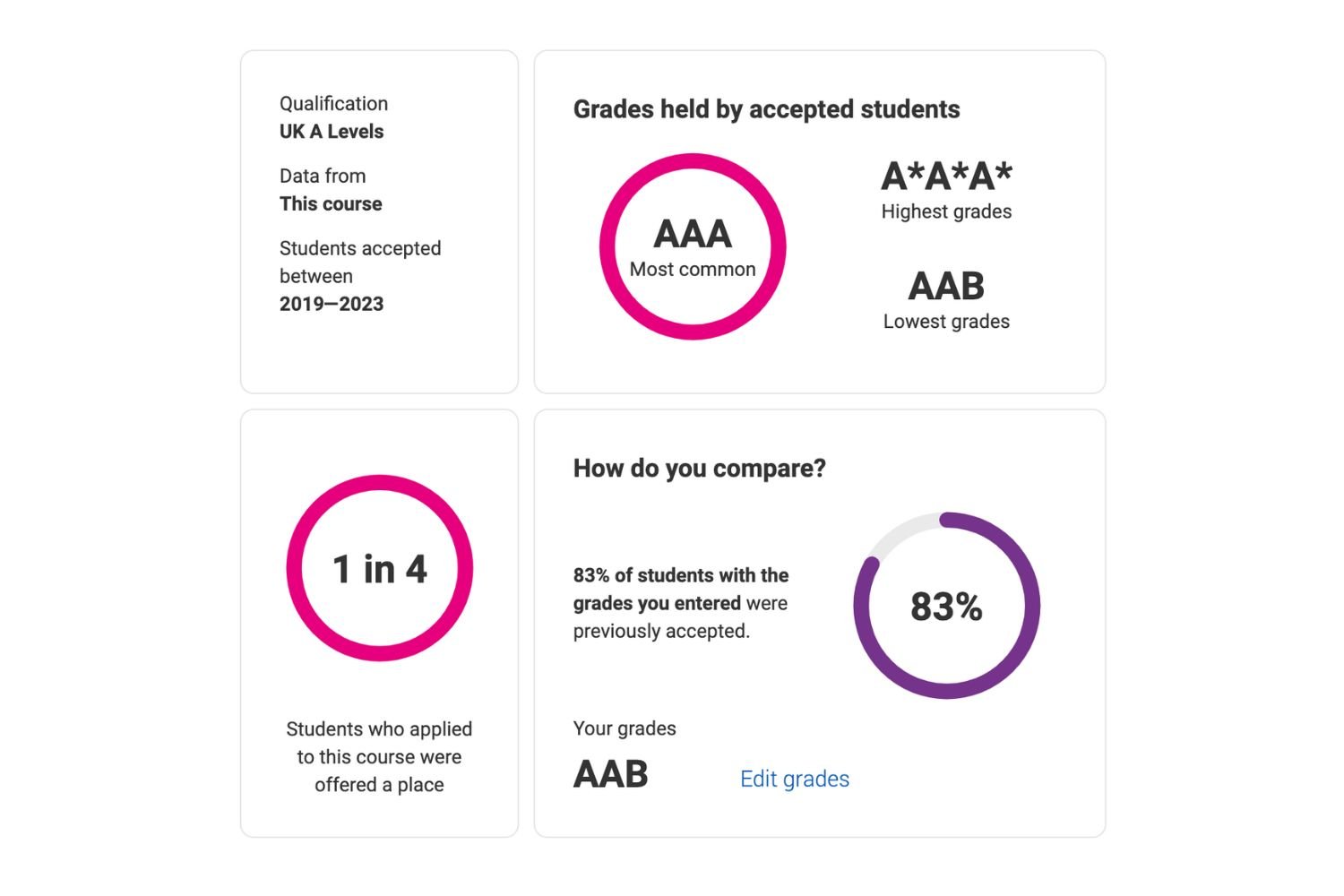

For each course, under a heading “Entry Grades Data (Beta)”, you’ll see several new bits of information:

Most common entry grades.

Highest entry grade, and Lowest entry grade.

The ratio of applicants who were offered a place.

And, if you put in your own grades (or predicted grades), it will tell you the percentage of students with your grades who were previously accepted.

What is missing is any attempt at giving an average entry grade, or any information about how the grade results were distributed.

A few notes on the data

First up, the data is based purely on English A-levels and BTEC results, and data is only used for students who took either three full A-levels, or a BTEC extended diploma. The information defaults to show A-levels, but you can change this to BTEC by entering your own grades and changing the qualification to BTEC.

Where enough data is available, it will be specific to a single course. Where there is not sufficient data, several courses might be amalgamated together.

Similarly, where enough data is available for the most recent year (2023 entry), this will be used, but if not, data from as far back as 2019 could be used.

For extra confusion, it includes students who may have had ‘contextual’ offers (these are lower offers, made to students from non-traditional backgrounds, who may have done extra pre-university programmes).

UCAS have taken care to exclude data for the highest and lowest 5% of admissions, so as to minimise the chances of rogue data skewing the results. This means that students who had exceptional circumstances taken into account, such as accidents or illness immediately before the exams, are likely to be excluded.

And, while those with 4 A-levels are presumably excluded, we can’t tell if those with three A-levels, plus an EPQ or perhaps an additional A-level are included or not.

So it’s fair to say that significant thought has gone into presenting the data, but it is, at best, approximate.

It gives a sense of the admissions picture over the previous years, but it is far too basic and insufficiently detailed to make any serious attempt at statistics analysis.

And most importantly of all, it gives literally no information at all about what will happen in the coming year.

So how useful is this for applicants?

Using this information when making initial five choices

As I wrote in Just how ambitious should you be with your initial five UCAS choices?, I suggest you have a couple of stretch choices, a couple of realistic options, and at least one very safe option.

This new information now presented by UCAS, can perhaps be used cautiously as part of your decisions over these initial five choices.

You see, if there is a large difference between the published entry grades and those most commonly achieved, it suggests that the course is not actually as selective as the university would want you to believe.

If there is little or no difference at all between the published grades and the most commonly achieved grades, then it indicates that the course really is as selective as they say.

If you combine this information with the ratio of applicants admitted, then you can start to get a sense of how genuinely competitive the course could be.

Those with a large difference in published entry grades vs historical grades and a large ratio of applicants admitted are clearly choices where you can be a little more optimistic of gaining a place.

It doesn’t mean that you’ll definitely get an offer, it just means that you are more likely to get an offer.

So, depending on your predicted grades, a course that might have been one of your ambitious/stretch choices, could become one of your realistic choices.

And of course, where you know that there are interviews, admissions tests, portfolios or auditions involved, you can use the offer ratio to deduce how competitive these elements actually are.

If 9 out of 10 applicants are offered places on a course that interviews, you can guess that the interview isn’t very selective after all. Whereas if only 1 in 5 applicants is offered a place, you’ll know that it's a tough process!

When choosing Firm and Insurance

I’ve written about making Firm and Insurance choices in Going from five to two choices, where I am super-clear that your Firm acceptance should be your first choice of course, while your Insurance choice should be a safe back-up option.

When making these choices, once again I think that the data could be super-useful.

At this stage, you don’t need to worry about the ratio of accepted students. Nor do you need to worry about the most common grades accepted. Rather, you are concerned with what is the lowest result you can achieve in your exams and still be accepted.

So, where the “Lowest grade” is much lower than the offer you have received, you can be optimistic that the university will be generous when it comes to exam results day. And in such cases, you can choose such an offer with a bit more confidence!

Note that I am using words like ‘optimistic’, ‘confidence’ etc, not ‘certain’, or ‘know’.

There are no certainties in admissions, and just because someone got in last year with certain grades does not mean that you will get in with the same grades this year.

So don’t throw caution to the wind; your Firm acceptance should still be your first choice, while your Insurance acceptance should still be a safe option.

Will it affect university behaviour in the future?

While it won’t affect current applicants, perhaps the most interesting question for advisers and future applicants is whether the publication of this data will affect the way universities present their entry qualifications in future years.

Universities want to appear competitive for entry, and for many, this data will blow a large hole in the myth.

While some courses ask for AAB and most of their entrants come in with AAB, you’ll find plenty of other courses that ask for AAB, but actually admit more students with CCC.

Universities who are genuinely competitive, and whose entry data matches their published entry requirements have nothing to fear from this data. In fact, quite the opposite; the data will benefit them, building trust with their applicants.

However, universities in the second category, where there is a large gap between published requirements and real entry data, will be placed in a very precarious position. If they start to present entry requirements that reflect reality, they risk losing many of the stronger students that they currently admit. If they don’t, they’ll potentially be seen as deliberately trying to mislead; eroding applicant trust.

This applies not just to universities who have traditionally been known as “recruiting” universities, but also to a whole load of universities and courses in the middle.

I think there will inevitably have to be a move towards more honest published admissions grades, but the cost for the sector will be a further polarisation between the genuinely competitive universities and course, and the rest.

Either way, students are pretty savvy. If they are capable of getting AAB, they’ll want to go to a university and a course where they will be studying alongside similarly able students, and benefit from the reputation that brings.

The price to pay for the sector may well be that many of the excellent and well established universities that currently sit in the middle of the sector for demand (and for entry requirements), could effectively be forced to lower their published entry requirements, and find it increasingly hard to compete.

This will just add further fuel to the fire of demand for the competitive universities, making a small handful of universities even more difficult to get into!

For further reading, you might like to have a look at: Why are some universities so ridiculously hard to get into?